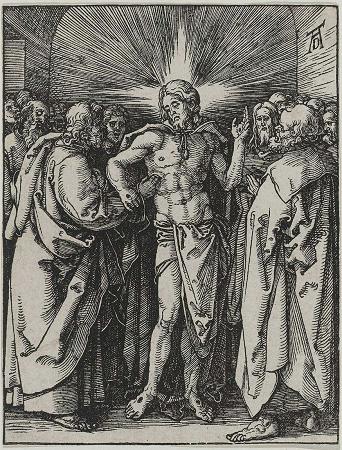

Doubting Thomas. A doubting Thomas is a skeptic who refuses to believe without direct personal experience; a reference to the Gospel of John's depiction of the Apostle Thomas, who, in John's account, refused to believe the resurrected Jesus had appeared to the ten other apostles until he could see and feel Jesus' crucifixion wounds. In art, the episode has been frequently depicted since at least the 5th century, with its depiction reflecting a range of theological interpretations. The episode is related in the Gospel of John chapter 20, though not in the three synoptic Gospels.The King James Version text is: 24 But Thomas, one of the twelve, called Didymus, was not with them when Jesus came. 25 The other disciples therefore said unto him, We have seen the Lord. But he said unto them, Except I shall see in his hands the print of the nails, and put my finger into the print of the nails, and thrust my hand into his side, I will not believe. 26 ¶ And after eight days again his disciples were within, and Thomas with them: came Jesus, the doors being shut, and stood in the midst, and said, Peace unto you. 27 Then saith he to Thomas, Reach hither thy finger, and behold my hands; and reach hither thy hand, and thrust into my side: and be not faithless, but believing. 28 And Thomas answered and said unto him, My Lord and my God. 29 Jesus saith unto him, Thomas, because thou hast seen me, thou hast believed: blessed they that have not seen, and have believed. Commentators have noted that John avoids saying whether Thomas actually did thrust his hand in. Before the Protestant Reformation the usual belief, reflected in artistic depictions, was that he had done so, which most Catholic writers continued to believe, while Protestant writers often thought that he had not. Regardless of the question of whether Thomas had felt as well as seen the physical evidence of the Resurrection of Jesus, the Catholic interpretation was that, although Jesus asserts the superiority of those who have faith without physical evidence, he was nonetheless willing to show Thomas his wound, and let him feel it. This was used by theologians as biblical encouragement for the use of physical experiences such as pilgrimages, veneration of relics and ritual in reinforcing Christian beliefs. Protestant theologians emphasized Jesus' statement of the superiority of faith alone, although the evangelical-leaning Anglican Thomas Hartwell Horne, in his widely read Introduction to the Critical Study and Knowledge of the Holy Scriptures treated Thomas's incredulity, which he extended somewhat to the other apostles, approvingly, as evidence both of the veracity of the gospels, as a forger would be unlikely to have invented it, and of their proper suspicion of the seemingly impossible, demonstrating their reliability as witnesses. In the early church, Gnostic authors were very insistent that Thomas did not actually examine Jesus, and elaborated on this in apocryphal accounts, perhaps tending to push their non-Gnostic opponents in the other direction. The theological interpretation of the episode has concentrated on it as a demonstration of the reality of the resurrection, but as early as the writings of the 4th-and 5th-century saints John Chrysostom and Cyril of Alexandria it had been given a eucharistic interpretation, seen as an allegory of the sacrament of the Eucharist, what remained a recurring theme in commentary. In art this subject, formally termed The Incredulity of Saint Thomas, has been common since at least the early 6th century, when it appears in the mosaics at Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, and on the Monza ampullae. In those depictions, as later in the Baroque, the subject, normally depicted at the moment Thomas puts his fingers into Jesus' side, was used to emphasize the importance of physical experiences and evidences for the believer, as described above. The Ravenna mosaic introduces the motif of Jesus raising his hand high to reveal the wound in his side; his pose often, but not always, is such that the wounds on his hands can also be seen, and often those on his feet as well. The scene was used in a number of contexts in medieval art, including Byzantine icons. Where there was room all the apostles were often shown, and sometimes Thomas' acceptance of the Resurrection is shown, with Thomas kneeling and Jesus blessing him. This iconography leaves it unclear whether the moment shown follows an examination or not, but probably suggests that it does not, especially in Protestant art. From the late Middle Ages onwards a number of variations of the poses of the two figures occur. The typical touching representation formed one of a number of scenes sometimes placed around a central Crucifixion of Jesus, and is one of the scenes shown on the Irish Muiredach's High Cross, and the subject of a large relief in the famous Romanesque sculpted cloister at the Abbey of Santo Domingo de Silos.

more...