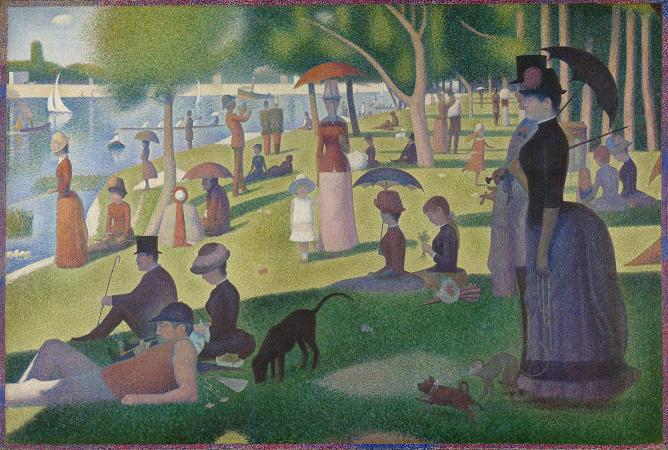

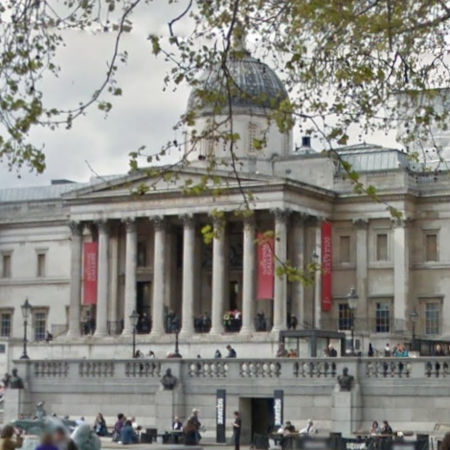

Bathers at Asnieres (1884). Oil on panel. 201 x 300. Bathers at Asnières is an 1884 oil-on-canvas painting by the French artist Georges Pierre Seurat, the first of his two masterpieces on the monumental scale. The canvas is of a suburban, placid Parisian riverside scene. Isolated figures, with their clothes piled sculpturally on the riverbank, together with trees, austere boundary walls and buildings, and the River Seine are presented in a formal layout. A combination of complex brushstroke techniques, and a meticulous application of contemporary colour theory bring to the composition a sense of gentle vibrancy and timelessness. Seurat completed the painting of Bathers at Asnières in 1884, when he was twenty-four years old. He applied to the jury of the Salon of the same year to have the work exhibited there, but the jury rejected it. The Bathers continued to puzzle many of Seurat’s contemporaries, and the picture was not widely acclaimed until many years after the death of the artist at the age of just thirty-one. An appreciation of the painting’s merits grew during the twentieth century, and today it hangs in the National Gallery, London, where it is considered one of the highlights of the gallery’s collection of paintings. The spot depicted is just short of four miles from the centre of Paris. In fact, the figures on the river-bank are not in the commune of Asnières, but in Courbevoie, the commune bordering Asnières to the west. The bathers are in the River Seine. The slope forming most of the left hand side of the painting was known as the Côte des Ajoux, near the end of the rue des Ajoux, on the north bank of the river. Opposite is the island of la Grande Jatte, the east tip of which is shown as the slope and the trees to the right, and which Seurat has pictorially extended beyond its actual length. The Asnières railway bridge and the industrial buildings of Clichy are in the background. Locations such as this one were sometimes shown on French nineteenth century maps as Baignade. Many artists painted canvases from this stretch of the Seine during the 1880s. As well as the Bathers, some of Seurat’s better known works to come from the vicinity include his The Seine at Courbevoie, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, and The Bridge at Courbevoie. Seurat uses a variety of means to suggest the baking heat of a summer’s day at the riverside. A hot haze softens the edges of the trees in the middle-distance and washes out colour from the bridges and factories in the background—the blue of the sky at the horizon is paled almost to whiteness. A shimmering appearance at the surface of Bathers at Asnières subtly reinforces this saturating heat and sunlight. Writing about these effects, the art historian Roger Fry reported his view that, no one could render this enveloping with a more exquisitely tremulous sensibility, a more penetrating observation or more unfailing consistency, than Seurat. The isolated figures are given statuesque but largely unmodeled treatment, and their skin and their clothes are clean, with a waxy finish. They appear unselfconscious, at ease in their environment, and—with the possible exception of the boy to the bottom right—are locked in a pensive and solitary reverie. Horizontal and vertical lines at the middle and far distance contrast with arched backs and the relaxed postures of the figures toward the front. These postures, angles of heads, directions of gaze, and positions of limbs are repeated among the figures, giving the group a rhythmic unity. Distinctively coloured forms in close proximity, such as the grouping of horse-chestnut colours of the clothes on the bank, and the grouping of oranges of the boys in the water, add to the stability of the work—an effect reinforced in the cluster of shadows to the left on the bank, and the un-verisimilar play of light around the bathing figures. At the time of this painting, urban development in Paris was proceeding at a very rapid pace. The population of Paris had doubled from one million in 1850 to two million in 1877, and the population of Asnières had almost doubled in just ten years to reach 14,778 in 1886. The reality of the often unpleasant or dangerous conditions in which industrial workers laboured had already been fully taken on by painters, such as in—for instance—Monet’s painting of 1875, Men unloading coal, which in fact shows the bridges at Asnières as they were almost a decade before Seurat painted them.

more...