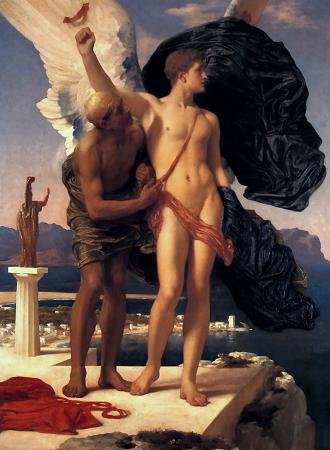

Daedalus. In Greek mythology, Daedalus was a skillful craftsman and artist, and was seen as a symbol of wisdom, knowledge, and power. He is the father of Icarus, the uncle of Perdix, and possibly also the father of Iapyx, although this is unclear. He invented and built the labyrinth for king Minos of Crete, but shortly after finishing it king Minos had Daedalus imprisoned within the labyrinth. He and his son Icarus devised a plan to escape by using wings made of wax that Daedalus had invented. They escaped, but sadly Icarus did not heed his father's warnings and flew too close to the sun. The wax melted and Icarus fell to his death. This left Daedalus heartbroken, but instead of giving up he flew to the island of Sicily. Daedalus's parentage was supplied as a later addition, providing him with a father in Metion, Eupalamus, or Palamaon, and a mother, Alcippe, Iphinoe, or Phrasmede. Daedalus had two sons: Icarus and Iapyx, along with a nephew either Talos or Perdix. Athenians transferred Cretan Daedalus to make him Athenian-born, the grandson of the ancient king Erechtheus, claiming that Daedalus fled to Crete after killing his nephew Talos. Over time, other stories were told of Daedalus. Daedalus is first mentioned by Homer as the creator of a wide dancing-ground for Ariadne. He also created the Labyrinth on Crete, in which the Minotaur was kept. In the story of the labyrinth as told by the Hellenes, the Athenian hero Theseus is challenged to kill the Minotaur, finding his way with the help of Ariadne's thread. Daedalus' appearance in Homer is in an extended metaphor, plainly not Homer's invention, Robin Lane Fox observes: He is a point of comparison and so he belongs in stories which Homer's audience already recognized. In Bronze Age Crete, an inscription da-da-re-jo-de has been read as referring to a place at Knossos, and a place of worship. In Homer's language, daidala refers to finely crafted objects. They are mostly objects of armor, but fine bowls and furnishings are also daidala, and on one occasion so are the bronze-working of clasps, twisted brooches, earrings and necklaces made by Hephaestus while cared for in secret by the goddesses of the sea. Ignoring Homer, later writers envisaged the Labyrinth as an edifice rather than a single dancing path to the center and out again, and gave it numberless winding passages and turns that opened into one another, seeming to have neither beginning nor end. Ovid, in his Metamorphoses, suggests that Daedalus constructed the Labyrinth so cunningly that he himself could barely escape it after he built it. Daedalus built the labyrinth for King Minos, who needed it to imprison his wife's son the Minotaur. The story is told that Poseidon had given a white bull to Minos so that he might use it as a sacrifice. Instead, Minos kept it for himself; and in revenge, Poseidon, with the help of Aphrodite, made Pasiphae, King Minos's wife, lust for the bull. For Pasiphae, as Greek mythologers interpreted it, Daedalus also built a wooden cow so she could mate with the bull, for the Greeks imagined the Minoan bull of the sun to be an actual, earthly bull, the slaying of which later required a heroic effort by Theseus. This story thus encourages others to consider the long-term consequences of their own inventions with great care, lest those inventions do more harm than good. As in the tale of Icarus' wings, Daedalus is portrayed assisting in the creation of something that has subsequent negative consequences, in this case with his creation of the monstrous Minotaur's almost impenetrable Labyrinth, which made slaying the beast an endeavour of legendary difficulty. The most familiar literary telling explaining Daedalus' wings is a late one, that of Ovid: in his Metamorphoses Daedalus was shut up in a tower to prevent the knowledge of his Labyrinth from spreading to the public. He could not leave Crete by sea, as the king kept a strict watch on all vessels, permitting none to sail without being carefully searched. Since Minos controlled the land and sea routes, Daedalus set to work to fabricate wings for himself and his young son Icarus. He tied feathers together, from smallest to largest so as to form an increasing surface. He secured the feathers at their midpoints with string and at their bases with wax, and gave the whole a gentle curvature like the wings of a bird. When the work was done, the artist, waving his wings, found himself buoyed upward and hung suspended, poising himself on the beaten air. He next equipped his son in the same manner, and taught him how to fly. When both were prepared for flight, Daedalus warned Icarus not to fly too high, because the heat of the sun would melt the wax, nor too low, because the sea foam would soak the feathers.

more...