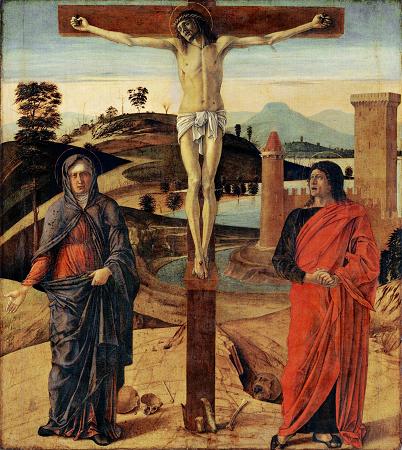

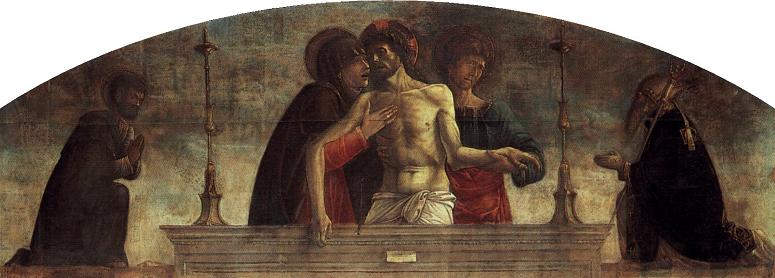

Giovanni Bellini (1426 - 1516). Giovanni Bellini was an Italian Renaissance painter, probably the best known of the Bellini family of Venetian painters. His father was Jacopo Bellini, his brother was Gentile Bellini, and his brother-in-law was Andrea Mantegna. He was considered to have revolutionized Venetian painting, moving it towards a more sensuous and colouristic style. Through the use of clear, slow-drying oil paints, Giovanni created deep, rich tints and detailed shadings. His sumptuous coloring and fluent, atmospheric landscapes had a great effect on the Venetian painting school, especially on his pupils Giorgione and Titian. Giovanni Bellini was born in Venice. He was brought up in his father's house, and always lived and worked in the closest fraternal relation with his brother Gentile. Up until the age of nearly thirty we find in his work a depth of religious feeling and human pathos which is his own. His paintings from the early period are all executed in the old tempera method: the scene is softened by a new and beautiful effect of romantic sunrise color. In a changed and more personal manner, he drew Dead Christ pictures. with less harshness of contour, a broader treatment of forms and draperies and less force of religious feeling. Giovanni's early works have often been linked both compositionally and stylistically to those of his brother-in-law, Andrea Mantegna. In 1470 Giovanni received his first appointment to work along with his brother and other artists in the Scuola di San Marco, where among other subjects he was commissioned to paint a Deluge with Noah's Ark. None of the master's works of this kind, whether painted for the various schools or confraternities or for the ducal palace, has survived. To the decade following 1470 must probably be assigned the Transfiguration now in the Capodimonte Museum of Naples, repeating with greatly ripened powers and in a much serener spirit the subject of his early effort at Venice. Also the great altar-piece of the Coronation of the Virgin at Pesaro, which would seem to be his earliest effort in a form of art previously almost monopolized in Venice by the rival school of the Vivarini. As is the case with a number of his brother, Gentile's public works of the period, many of Giovanni's great public works are now lost. The still more famous altar-piece painted in tempera for a chapel in the church of S. Giovanni e Paolo, where it perished along with Titian's Peter Martyr and Tintoretto's Crucifixion in the disastrous fire of 1867. After 1479-1480 much of Giovanni's time and energy must also have been taken up by his duties as conservator of the paintings in the great hall of the Doge's Palace. The importance of this commission can be measured by the payment Giovanni received: he was awarded, first the reversion of a broker's place in the Fondaco dei Tedeschi, and afterwards, as a substitute, a fixed annual pension of eighty ducats. Besides repairing and renewing the works of his predecessors he was commissioned to paint a number of new subjects, six or seven in all, in further illustration of the part played by Venice in the wars of Frederick Barbarossa and the pope. These works, executed with much interruption and delay, were the object of universal admiration while they lasted, but not a trace of them survived the fire of 1577; neither have any other examples of his historical and processional compositions come down, enabling us to compare his manner in such subjects with that of his brother Gentile. Of the other, the religious class of his work, including both altar-pieces with many figures and simple Madonnas, a considerable number have been preserved. They show him gradually throwing off the last restraints of the Quattrocento manner; gradually acquiring a complete mastery of the new oil medium introduced in Venice by Antonello da Messina about 1473, and mastering with its help all, or nearly all, the secrets of the perfect fusion of colors and atmospheric gradation of tones. The old intensity of pathetic and devout feeling gradually fades away and gives place to a noble, if more worldly, serenity and charm. The enthroned Virgin and Child become tranquil and commanding in their sweetness; the personages of the attendant saints gain in power, presence and individuality; enchanting groups of singing and viol-playing angels symbolize and complete the harmony of the scene. The full splendour of Venetian color invests alike the figures, their architectural framework, the landscape and the sky. An interval of some years, no doubt chiefly occupied with work in the Hall of the Great Council, seems to separate the San Giobbe Altarpiece, and that of the church of San Zaccaria at Venice.

more...