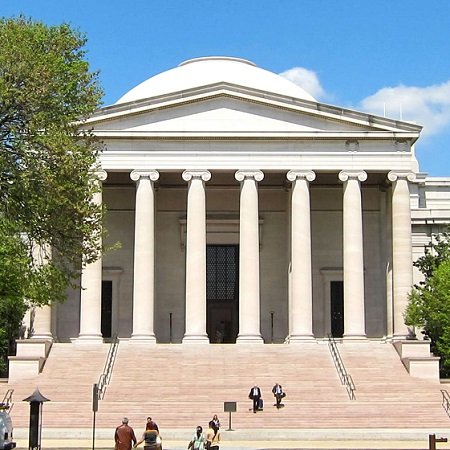

Annunciation (c1435). Oil on canvas transferred from panel. 90 x 34. The Annunciation is an oil painting by the Early Netherlandish master Jan van Eyck, from around 1434-1436. The panel is housed in the National Gallery of Art, in Washington D.C. It was originally on panel but has been transferred to canvas. It is thought that it was the left wing of a triptych; there has been no sighting of the other wings since before 1817. The annunciation is a highly complex work, whose iconography is still debated by art historians. The picture depicts the Annunciation by the Archangel Gabriel to the Virgin Mary that she will bear the son of God. The inscription shows his words: or Hail, full of grace. She modestly draws back and responds, or Behold the handmaiden of the Lord. The words appear upside down because they are directed to God and are therefore inscribed with a God's-eye view. The Seven gifts of the Holy Spirit descend to her on seven rays of light from the upper window to the left, with the dove symbolizing the Holy Spirit following the same path; This is the moment God's plan for salvation is set in motion. Through Christ's human incarnation the old era of the Law is transformed into a new era of Grace. The setting develops this theme. Mary was believed in the Middle Ages to have been a very studious girl who was engaged by the Temple of Jerusalem with other selected maidens to spin new curtains for the Holy of Holies. The book she is reading here is too large to be a lady's Book of Hours; as in other paintings she is engaged in serious study in a part of the temple. The van Eycks were almost the first to use this setting in panel painting, but it appears earlier in illuminated manuscripts, and in an altarpiece of 1397 from the same monastery for which this painting was probably ordered. The architecture moves from older, round Romanesque forms above, to pointed Gothic arches below, with the higher levels largely in darkness, and the floor level well-lit. The gloom of the Old Covenant is about to be succeeded by the light of the New Covenant. The flat timber roof is in poor repair, with planks out of place. The use of Romanesque architecture to identify Jewish rather than Christian settings is a regular feature of the paintings of van Eyck and his followers, and other paintings show both styles in the same building in a symbolic way. The decoration of the temple is naturally all derived from the Old Testament, but the subjects shown are those believed in the Middle Ages to prefigure the coming of Christ the Messiah. In the floor tiles David's slaying of Goliath, foretells Christ's triumph over the devil. Behind this, Samson pulls down the Temple of the Philistines, prefiguring both the Crucifixion and the Last Judgement, according to medieval authorities. To the left, Delilah is cutting Samson's hair, and behind he slays the Philistines. The death of Absalom and possibly that of Abimelech are identified by some art historians, although only tiny sections are visible. Erwin Panofsky, who developed much of this analysis, proposed a scheme for the significance of the astrological symbols in the round border tiles, and other versions have been suggested. The rear wall has a single stained glass window, where Jehovah stands, above triple plain-glazed windows below, which perhaps suggest the Christian trinity. On either side of the single window are dim wall-paintings of the Finding of Moses by Pharaoh's daughter, and Moses receiving the Ten Commandments. Below them are roundels with Isaac and Jacob, for which various symbolic functions have been proposed. The lilies are a traditional attribute of Mary, standing for purity. The empty stool may be an empty throne, a symbol for Christ going back to early Byzantine art. It has been suggested that Mary has been given the features of Isabella of Portugal, wife of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, who may well have commissioned the painting from van Eyck, his court painter. Mary wears a robe in her usual blue, which is trimmed in ermine, reserved for royalty, which would suit this theory, although the Middle Ages placed great emphasis on Mary's royal descent in any case. As is usual, especially in the North, Mary's features are less attractive than those of Gabriel; being a sexless angel there was considered to be no possibility of his beauty causing inappropriate thoughts in the onlooker. Neither figure has a halo; these were being dispensed with in Early Netherlandish art in the interests of realism-eventually the Italians would follow. Mary's posture is ambiguous; it is not clear if she is standing, kneeling or sitting. Many writers, including Hand, call the figures over-large compared to the architecture.

more...