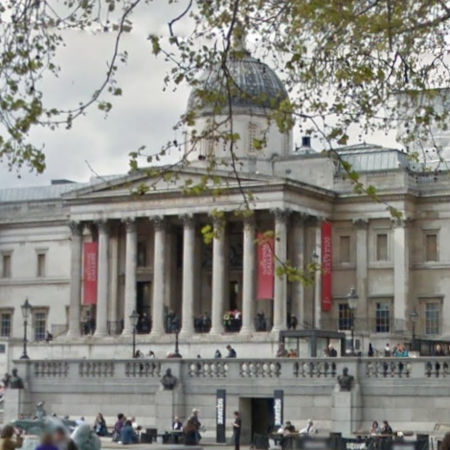

Arnolfini Marriage (1434). Oil on panel. 82 x 60. The Arnolfini Portrait is a 1434 oil painting on oak panel by the Early Netherlandish painter Jan van Eyck. It forms a full-length double portrait, believed to depict the Italian merchant Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini and his wife, presumably in their residence at the Flemish city of Bruges. It is considered one of the most original and complex paintings in Western art, because of its beauty, complex iconography, geometric orthogonal perspective, and expansion of the picture space with the use of a mirror. According to Ernst Gombrich in its own way it was as new and revolutionary as Donatello's or Masaccio's work in Italy. A simple corner of the real world had suddenly been fixed on to a panel as if by magic. For the first time in history the artist became the perfect eye-witness in the truest sense of the term. The portrait has been considered by Erwin Panofsky and some other art historians as a unique form of marriage contract, recorded as a painting. Signed and dated by van Eyck in 1434, it is, with the Ghent Altarpiece by the same artist and his brother Hubert, the oldest very famous panel painting to have been executed in oils rather than in tempera. The painting was bought by the National Gallery in London in 1842. Van Eyck used the technique of applying layer after layer of thin translucent glazes to create a painting with an intensity of both tone and colour. The glowing colours also help to highlight the realism, and to show the material wealth and opulence of Arnolfini's world. Van Eyck took advantage of the longer drying time of oil paint, compared to tempera, to blend colours by painting wet-in-wet to achieve subtle variations in light and shade to heighten the illusion of three-dimensional forms. The medium of oil paint also permitted van Eyck to capture surface appearance and distinguish textures precisely. He also rendered the effects of both direct and diffuse light by showing the light from the window on the left reflected by various surfaces. It has been suggested that he used a magnifying glass in order to paint the minute details such as the individual highlights on each of the amber beads hanging beside the mirror. The illusionism of the painting was remarkable for its time, in part for the rendering of detail, but particularly for the use of light to evoke space in an interior, for its utterly convincing depiction of a room, as well of the people who inhabit it. Whatever meaning is given to the scene and its details, and there has been much debate on this, according to Craig Harbison the painting is the only fifteenth-century Northern panel to survive in which the artist's contemporaries are shown engaged in some sort of action in a contemporary interior. It is indeed tempting to call this the first genre painting-a painting of everyday life-of modern times. The painting is generally in very good condition, though with small losses of original paint and damages, which have mostly been retouched. Infrared reflectograms of the painting show many small alterations, or pentimenti, in the underdrawing: to both faces, to the mirror, and to other elements. The couple are shown in an upstairs room with a chest and a bed in it during early summer as indicated by the fruit on the cherry tree outside the window. The room probably functioned as a reception room, as it was the fashion in France and Burgundy where beds in reception rooms were used as seating, except, for example, when a mother with a new baby received visitors. The window has six interior wooden shutters, but only the top opening has glass, with clear bulls-eye pieces set in blue, red and green stained glass. The two figures are very richly dressed; despite the season both their outer garments, his tabard and her dress, are trimmed and fully lined with fur. The furs may be the especially expensive sable for him and ermine or miniver for her. He wears a hat of plaited straw dyed black, as often worn in the summer at the time. His tabard was more purple than it appears now and may be intended to be silk velvet. Underneath he wears a doublet of patterned material, probably silk damask. Her dress has elaborate dagging on the sleeves, and a long train. Her blue underdress is also trimmed with white fur. Although the woman's plain gold necklace and the rings that both wear are the only jewellery visible, both outfits would have been enormously expensive, and appreciated as such by a contemporary viewer. There may be an element of restraint in their clothes befitting their merchant status-portraits of aristocrats tend to show gold chains and more decorated cloth, although the restrained colours of the man's clothing correspond to those favoured by Duke Phillip of Burgundy.

more...