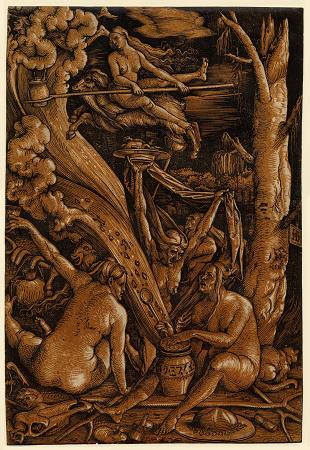

Witches' Sabbath. The Witches' Sabbath is a term applied to a gathering of those considered to practice witchcraft and other rites. Prior to the late 19th century, it is difficult to locate any English use of the term sabbath to denote a gathering of witches. The phrase is used by Henry Charles Lea's in his History of the Inquisition. Writing in 1900, German historian Joseph Hansen who was a correspondent and a German translator of Lea's work, frequently uses the shorthand phrase hexensabbat to interpret medieval trial records, though any consistently recurring term is noticeably rare in the copious Latin sources Hansen also provides. Lea and Hansen's influence may have led to a broader use of the shorthand phrase, including in English. Prior to Hansen, German use of the term also seems to have been rare and the compilation of German folklore by Jakob Grimm in the 1800s seems to contain no mention of hexensabbat or any other form of the term sabbat relative to fairies or magical acts. The contemporary of Grimm and early historian of witchcraft, WG Soldan also doesn't seem to use the term in his history. In contrast to German and English counterparts, French writers occasionally did use the term and there would seem to be roots to inquisitorial persecution of the Waldensians. In 1124, the term inzabbatos is used to describe the Waldensians in Northern Spain. In 1438 and 1460 seemingly related terms synagogam and synagogue of Sathan are used to describe Waldensians by inquisitors in France which could be a reference to Revelations 2:9. Writing in Latin in 1458, Francophone author Nicolas Jacquier applies synagogam fasciniorum to what he considers a gathering of witches. About 150 years later, at the peak of the witch-phobia and the persecutions which led to the burning to death of an estimated 50,000 persons, with roughly 80% being women, the witch-phobic French and Francophone writers still seem to be the only ones using these related terms, though still infrequently and sporadically in most cases. Lambert Daneau uses sabbatha one time as Synagogas quas Satanica sabbatha. Jean Bodin uses it three times. Nicholas Remi uses it as well as synagoga. In 1611, Jacques Fontaine uses sabat five times writing in French and in a way that would seem to correspond with modern usage. Writing a witch-phobic work in French the following year, Pierre de Lancre seems to use the term more frequently than anyone before. More than two hundred years after Pierre de Lancre, French writer Lamothe-Langon, whose character and scholarship was questioned in the 1970s, uses the term in translating into French a handful of documents from the inquisition in Southern France. Joseph Hansen cited Lamothe-Langon as one of many sources. In modern Judaism, Shabbat is the rest day celebrated from Friday evening to Saturday nightfall; in modern Christianity, Sabbath refers to Sunday, or to a time period similar to Sabbath in the seventh-day church minority. In connection with the medieval beliefs in the evil power of witches and in the malevolence of Jews and Judaizing heretics, satanic gatherings of witches were by outsiders called sabbats, synagogues, or convents.Local variations of the name given to witches' gatherings were frequent. Perhaps the earliest work that mentions a something like a gathering that might be interpreted, from the Christian point of view, as witches sabbath is Canon Episcopi and later included in Burchard of Worms's collection in the 11th century. The Canon Episcopi forwards the Christian doctrine that things of this nature were false delusions and did not occur in reality. Errores Gazariorum later evoked the Sabbat, in 1452. Helping to publicize belief in and the threat of the Witches' Sabbath was the extensive preaching of the popular Franciscan reformer, Saint Bernardino of Siena, whose widely circulating sermons contain various references to the sabbath as it was then conceived and hence represent valuable early sources into the history of this phenomenon. Some allusions to meetings of more than one witch and possibly other demons are made in the Inquistors' manual of witch-hunting, the Malleus Maleficarum. Nevertheless, it was during the Renaissance when Sabbath folklore was most popular, more books on them were published, and more people lost their lives when accused of participating. Commentarius de Maleficiis, by Peter Binsfeld, cites accusation of participation in Sabbaths as a proof of guiltiness in an accusation for the practice of witchcraft.

more...