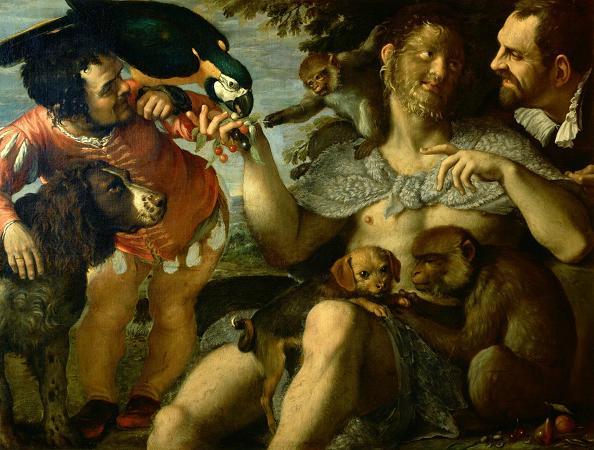

Jester. A jester, court jester, or fool, was historically an entertainer during the medieval and Renaissance eras who was a member of the household of a nobleman or a monarch employed to entertain him and his guests. A jester was also an itinerant performer who entertained common folk at fairs and markets. Jesters are also modern-day entertainers who resemble their historical counterparts. Jesters in medieval times are often thought to have worn brightly coloured clothes and eccentric hats in a motley pattern and their modern counterparts usually mimic this costume. Jesters entertained with a wide variety of skills: principal among them were song, music, and storytelling, but many also employed acrobatics, juggling, telling jokes, such as puns, stereotypes, and imitation, and magic tricks. Much of the entertainment was performed in a comic style and many jesters made contemporary jokes in word or song about people or events well known to their audiences. The modern use of the English word jester did not come into use until the mid-16th century, during Tudor times. This modern term derives from the older form gestour, or jestour, originally from Anglo-Norman meaning storyteller or minstrel. Other earlier terms included fol, disour, buffoon and bourder. These terms described entertainers who differed in their skills and performances but who all shared many similarities in their role as comedic performers for their audiences. Early jesters were popular in Ancient Egypt, and entertained Egyptian pharaohs. The ancient Romans had a tradition of professional jesters, called balatrones. Balatrones were paid for their jests, and the tables of the wealthy were generally open to them for the sake of the amusement they afforded. Jesters were popular with the Aztec people in the 14th to 16th centuries. Many royal courts throughout English royal history employed entertainers and most had professional fools, sometimes called licensed fools. Entertainment included music, storytelling, and physical comedy. It has also been suggested they performed acrobatics and juggling. Henry VIII of England employed a jester named Will Sommers. His daughter Mary was entertained by Jane Foole. During the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I of England, William Shakespeare wrote his plays and performed with his theatre company the Lord Chamberlain's Men. Clowns and jesters were featured in Shakespeare's plays, and the company's expert on jesting was Robert Armin, author of the book Fooled upon Foole. In Shakespeare's Twelfth Night, Feste the jester is described as wise enough to play the fool. In Scotland, Mary, Queen of Scots had a jester called Nichola. Her son, King James VI of Scotland employed a jester called Archibald Armstrong. During his lifetime Armstrong was given great honours at court. He was eventually thrown out of the King's employment when he over-reached and insulted too many influential people. Even after his disgrace, books telling of his jests were sold in London streets. He held some influence at court still in the reign of Charles I and estates of land in Ireland. Anne of Denmark had a Scottish jester called Tom Durie. Charles I later employed a jester called Jeffrey Hudson who was very popular and loyal. Jeffrey Hudson had the title of Royal Dwarf because he was short of stature. One of his jests was to be presented hidden in a giant pie from which he would leap out. Hudson fought on the Royalist side in the English Civil War. A third jester associated with Charles I was called Muckle John. Scholar David Carlyon has cast doubt on the daring political jester, calling historical tales apocryphal, and concluding that popular culture embraces a sentimental image of the clown; writers reproduce that sentimentality in the jester, and academics in the Trickster, but it falters as analysis. Jesters could also give bad news to the King that no one else would dare deliver. In 1340, when the French fleet was destroyed at the Battle of Sluys by the English, Phillippe VI's jester told him the English sailors don't even have the guts to jump into the water like our brave French. After the Restoration, Charles II did not reinstate the tradition of the court jester, but he did greatly patronize the theatre and proto-music hall entertainments, especially favouring the work of Thomas Killigrew. Though Killigrew was not officially a jester, Samuel Pepys in his famous diary does call Killigrew The King's fool and jester, with the power to mock and revile even the most prominent without penalty. The last British nobles to keep jesters were the Queen Mother's family, the Bowes-Lyons.

more...