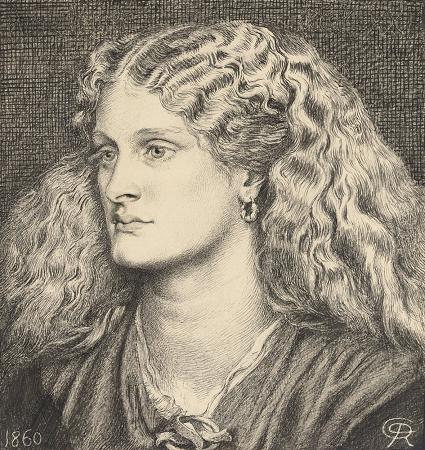

Awakening Conscience (c1853). Oil on canvas. 76 x 56. The Awakening Conscience is an oil-on-canvas painting by the English artist William Holman Hunt, one of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, which depicts a young woman rising from her position in the lap of a man and gazing transfixed out of the window of a room. The painting is in the collection of the Tate Britain in London. Initially, the painting appears to depict a momentary disagreement between husband and wife, but the title and a host of symbols within the painting make it clear that this is a mistress and her lover. The woman's clasped hands provide a focal point and the position of her left hand emphasizes the absence of a wedding ring. Around the room are dotted reminders of her kept status and her wasted life: the cat beneath the table toying with a bird; the clock concealed under glass; a tapestry which hangs unfinished on the piano; the threads which lie unravelled on the floor; the print of Frank Stone's Cross Purposes on the wall; Edward Lear's musical arrangement of Tennyson's poem Tears, Idle Tears which lies discarded on the floor, and the music on the piano, Thomas Moore's Oft in the Stilly Night, the words of which speak of missed opportunities and sad memories of a happier past. The discarded glove and top hat thrown on the table top suggest a hurried assignation. The room is too cluttered and gaudy to be in a Victorian family home; the bright colours, unscuffed carpet, and pristine, highly polished furniture speak of a room recently furnished for a mistress. Art historian Elizabeth Prettejohn notes that although the interior is now viewed as Victorian it still exudes the nouveau-riche vulgarity that would have made the setting distasteful to contemporary viewers. The painting's frame is decorated with further symbols: bells, marigolds, and a star above the girl's head. It also bears a verse from the Book of Proverbs: As he that taketh away a garment in cold weather, so is he that singeth songs to an heavy heart. The mirror on the rear wall provides a tantalizing glimpse out of the scene. The window, opening out onto a spring garden, in direct contrast to the images of entrapment within the room, is flooded with sunlight. The woman's face does not display a look of shock that she has been surprised with her lover; whatever attracts her is outside of both the room and her relationship. The Athenium commented in 1854: The author of The Bridge of Sighs could not have conceived a more painful-looking face. The details of the picture, the reflection of the spring trees in the mirror, the piano, the bronze under the lamp, are wonderfully true, but the dull indigoes and reds of the picture make it melancholy and appropriate, and not pleasing in tone. The sentiment is of the Ernest Maltravers School: to those who have an affinity for it, painful; to those who have not, repulsive. In some ways this painting is a companion to Hunt's Christian painting The Light of the World, a picture of Christ holding a lantern as he knocks on an overgrown handleless door which Hunt said represented the obstinately shut mind. The young woman here could be responding to that image, her conscience pricked by something outside of herself. Hunt intended this image to be The Light of the World's material counterpart in a picture representing in actual life the manner in which the appeal of the spirit of heavenly love calls a soul to abandon a lower life. In Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood Hunt wrote that Peggotty's search for Emily in David Copperfield had given him the idea for the composition and he began to visit different haunts of fallen girls looking for a suitable setting. He did not plan to recreate any particular scene from David Copperfield; he initially wanted to capture something more general: the loving seeker of the fallen girl coming upon the object of his search, but he reconsidered, deciding that such a meeting would engender different emotions in the girl than the repentance he wanted to show. He eventually settled on the idea that the girl's companion could be singing a song that suddenly reminded her of her former life and thereby act as the unknowing catalyst for her epiphany. The model for the girl was Annie Miller, who sat for many of the Pre-Raphaelites and to whom Hunt was engaged until 1859. The male figure may be based on Thomas Seddon or Augustus Egg, both painter friends of Hunt. The look on the girl's face in the modern painting is not the look of pain and horror that viewers saw when the painting was first exhibited, and which shocked and repulsed many of the contemporary critics.

more...