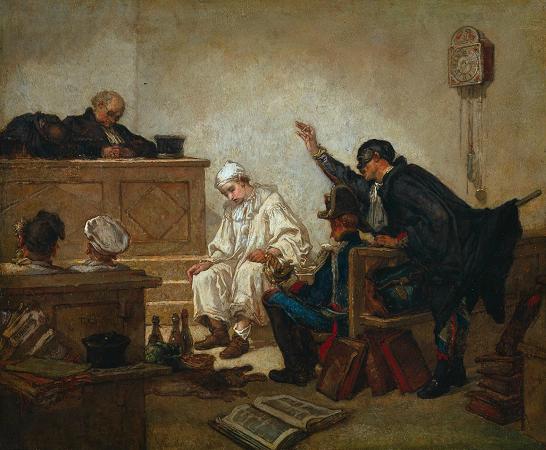

Pierrot. Pierrot is a stock character of pantomime and commedia dell'arte whose origins are in the late seventeenth-century Italian troupe of players performing in Paris and known as the Comédie-Italienne; the name is a diminutive of Pierre, via the suffix-ot. His character in contemporary popular culture, in poetry, fiction, and the visual arts, as well as works for the stage, screen, and concert hall, is that of the sad clown, pining for love of Columbine, who usually breaks his heart and leaves him for Harlequin. Performing unmasked, with a whitened face, he wears a loose white blouse with large buttons and wide white pantaloons. Sometimes he appears with a frilled collaret and a hat, usually with a close-fitting crown and wide round brim, more rarely with a conical shape like a dunce's cap. But most frequently, since his reincarnation under Jean-Gaspard Deburau, he wears neither collar nor hat, only a black skullcap. The defining characteristic of Pierrot is his naiveté: he is seen as a fool, often the butt of pranks, yet nonetheless trusting. It was a generally buffoonish Pierrot that held the European stage for the first two centuries of his history. And yet early signs of a respectful, even sympathetic attitude toward the character appeared in the plays of Jean-François Regnard and in the paintings of Antoine Watteau, an attitude that would deepen in the nineteenth century, after the Romantics claimed the figure as their own. For Jules Janin and Théophile Gautier, Pierrot was not a fool but an avatar of the post-Revolutionary People, struggling, sometimes tragically, to secure a place in the bourgeois world. And subsequent artistic/cultural movements found him equally amenable to their cause: the Decadents turned him, like themselves, into a disillusioned disciple of Schopenhauer, a foe of Woman and of callow idealism; the Symbolists saw him as a lonely fellow-sufferer, crucified upon the rood of soulful sensitivity, his only friend the distant moon; the Modernists converted him into a Whistlerian subject for canvases devoted to form and color and line. In short, Pierrot became an alter-ego of the artist, specifically of the famously alienated artist of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. His physical insularity; his poignant lapses into mutism, the legacy of the great mime Deburau; his white face and costume, suggesting not only innocence but the pallor of the dead; his often frustrated pursuit of Columbine, coupled with his never-to-be-vanquished unworldly naivete, all conspired to lift him out of the circumscribed world of the commedia dell'arte and into the larger realm of myth. Much of that mythic quality still adheres to the sad clown of the postmodern era. He is sometimes said to be a French variant of the sixteenth-century Italian Pedrolino, but the two types have little but their names and social stations in common. Both are comic servants, but Pedrolino, as a so-called first zanni, often acts with cunning and daring, an engine of the plot in the scenarios where he appears. Pierrot, on the other hand, as a second zanni, is a static character in his earliest incarnations, standing on the periphery of the action, dispensing advice that seems to him sage, and courting, unsuccessfully, his master's young daughter, Columbine, with bashfulness and indecision. His origins among the Italian players in France are most unambiguously traced to Molière's character, the lovelorn peasant Pierrot, in Don Juan, or The Stone Guest. In 1673, probably inspired by Moliere's success, the Comédie-Italienne made its own contribution to the Don Juan legend with an Addendum to The Stone Guest, which included Molière's Pierrot. Thereafter the character, sometimes a peasant, but more often now an Italianate second zanni, appeared fairly regularly in the Italians' offerings, his role always taken by one Giuseppe Giaratone, until the troupe was banished by royal decree in 1697. Among the French dramatists who wrote for the Italians and who gave Pierrot life on their stage were Jean Palaprat, Claude-Ignace Brugière de Barante, Antoine Houdar de la Motte, and the most sensitive of his early interpreters, Jean-François Regnard. He acquires there a very distinctive personality.

more...