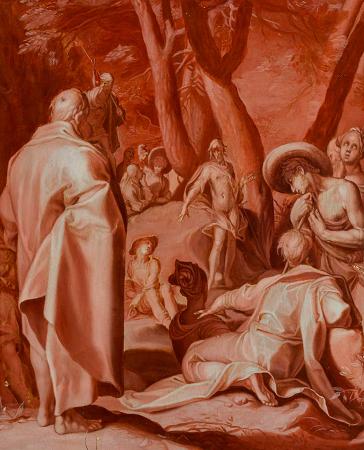

Northern Mannerism Painting. Northern Mannerism is the form of Mannerism found in the visual arts north of the Alps in the 16th and early 17th centuries. Styles largely derived from Italian Mannerism were found in the Netherlands and elsewhere from around the mid-century, especially Mannerist ornament in architecture; this article concentrates on those times and places where Northern Mannerism generated its most original and distinctive work. The three main centres of the style were in France, especially in the period 1530-50, in Prague from 1576, and in the Netherlands from the 1580s, the first two phases very much led by royal patronage. In the last 15 years of the century, the style, by then becoming outdated in Italy, was widespread across northern Europe, spread in large part through prints. In painting, it tended to recede rapidly in the new century, under the new influence of Caravaggio and the early Baroque, but in architecture and the decorative arts, its influence was more sustained. The sophisticated art of Italian Mannerism begins during the High Renaissance of the 1520s as a development of, a reaction against, and an attempt to excel, the serenely balanced triumphs of that style. As art historian Henri Zerner explains: The concept of Mannerism, so important to modern criticism and notably to the renewed taste for Fontainebleau art, designates a style in opposition to the classicism of the Italian Renaissance embodied above all by Andrea del Sarto in Florence and Raphael in Rome. The High Renaissance was a purely Italian phenomenon, and Italian Mannerism required both artists and an audience highly trained in the preceding Renaissance styles, whose conventions were often flouted in a knowing fashion. In Northern Europe, however, such artists, and such an audience, could hardly be found. The prevailing style remained Gothic, and different syntheses of this and Italian styles were made in the first decades of the 16th century by more internationally aware artists such as Albrecht Durer, Hans Burgkmair and others in Germany, and the misleadingly named school of Antwerp Mannerism, in fact unrelated to, and preceding, Italian Mannerism. Romanism was more thoroughly influenced by Italian art of the High Renaissance, and aspects of Mannerism, and many of its leading exponents had travelled to Italy. Netherlandish painting had been generally the most advanced in northern Europe since before 1400, and the best Netherlandish artists were better able than those of other regions to keep up with Italian developments, though lagging at a distance. For each succeeding generations of artists, the problem became more acute, as much Northern work continued to gradually assimilate aspects of Renaissance style, while the most advanced Italian art had spiralled into an atmosphere of self-conscious sophistication and complexity that must have seemed a world apart to Northern patrons and artists, but enjoyed a reputation and prestige that could not be ignored. France received a direct injection of Italian style in the form of the first School of Fontainebleau, where from 1530 several Florentine artists of quality were hired to decorate the royal Palace of Fontainebleau, with some French assistants being taken on. The most notable imports were Rosso Fiorentino, Francesco Primaticcio, Niccolo dell'Abbate, all of whom remained in France until their deaths. This conjunction succeeded in generating a native French style with strong Mannerist elements that was then able to develop largely on its own. Jean Cousin the Elder, for example, produced paintings, such as Eva Prima Pandora and Charity, that, with their sinuous, elongated nudes, drew palpably upon the artistic principles of the Fontainebleau school. Cousin's son Jean the Younger, most of whose works have not survived, and Antoine Caron both followed in this tradition, producing an agitated version of the Mannerist aesthetic in the context of the French Wars of Religion. The iconography of figurative works was mostly mythological, with a strong emphasis on Diana, goddess of the hunting that was the original function of Fontainebleau, and namesake of Diane de Poitiers, mistress and muse of Henry II, and keen huntress herself. Her slim, long-legged and athletic figure became fixed in the erotic imaginary. Other parts of Northern Europe did not have the advantage of such intense contact with Italian artists, but the Mannerist style made its presence felt through prints and illustrated books, the purchases of Italian works by rulers and others, artists' travels to Italy, and the example of individual Italian artists working in the North.

more...