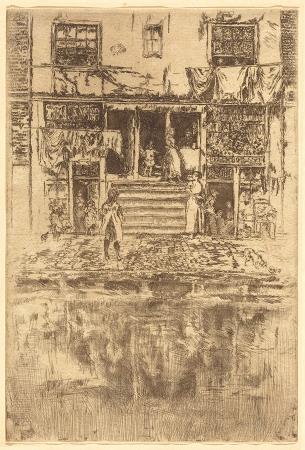

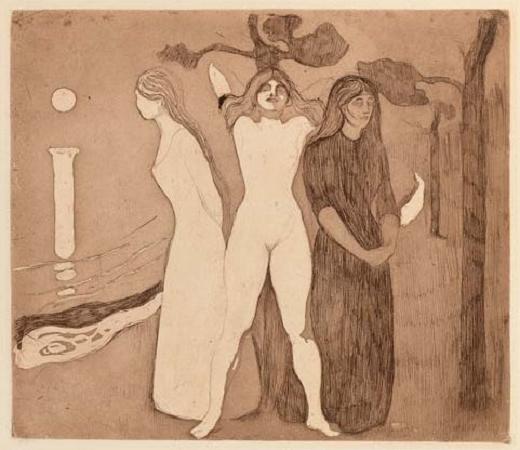

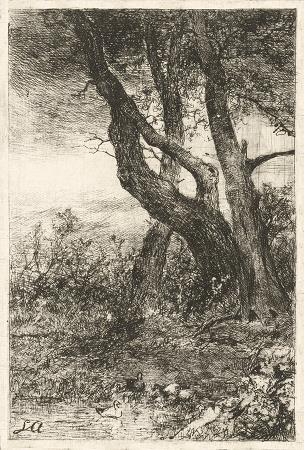

Etching. Etching is traditionally the process of using strong acid or mordant to cut into the unprotected parts of a metal surface to create a design in intaglio in the metal. In modern manufacturing, other chemicals may be used on other types of material. As a method of printmaking, it is, along with engraving, the most important technique for old master prints, and remains in wide use today. In a number of modern variants such as microfabrication etching and photochemical milling it is a crucial technique in much modern technology, including circuit boards. In traditional pure etching, a metal plate is covered with a waxy ground which is resistant to acid. The artist then scratches off the ground with a pointed etching needle where he or she wants a line to appear in the finished piece, so exposing the bare metal. The échoppe, a tool with a slanted oval section, is also used for swelling lines. The plate is then dipped in a bath of acid, technically called the mordant or etchant, or has acid washed over it. The acid bites into the metal to a depth depending on time and acid strength, leaving behind the drawing skillfully carved into the wax on the plate. The remaining ground is then cleaned off the plate. For first and renewed uses the plate is inked in any chosen non-corrosive ink all over and the surface ink drained and wiped clean, leaving ink in the etched forms. The plate is then put through a high-pressure printing press together with a sheet of paper. The paper picks up the ink from the etched lines, making a print. The process can be repeated many times; typically several hundred impressions could be printed before the plate shows much sign of wear. The work on the plate can be added to or repaired by re-waxing and further etching; such an etching may have been used in more than one state. Etching has often been combined with other intaglio techniques such as engraving or aquatint. Main article: Old master print Etching by goldsmiths and other metal-workers in order to decorate metal items such as guns, armour, cups and plates has been known in Europe since the Middle Ages at least, and may go back to antiquity. The elaborate decoration of armour, in Germany at least, was an art probably imported from Italy around the end of the 15th century, little earlier than the birth of etching as a printmaking technique. Printmakers from the German-speaking lands and Central Europe perfected the art and transmitted their skills over the Alps and across Europe. The process as applied to printmaking is believed to have been invented by Daniel Hopfer of Augsburg, Germany. Hopfer was a craftsman who decorated armour in this way, and applied the method to printmaking, using iron plates. Apart from his prints, there are two proven examples of his work on armour: a shield from 1536 now in the Real Armeria of Madrid and a sword in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum of Nuremberg. An Augsburg horse armour in the German Historical Museum, Berlin, dating to between 1512 and 1515, is decorated with motifs from Hopfer's etchings and woodcuts, but this is no evidence that Hopfer himself worked on it, as his decorative prints were largely produced as patterns for other craftsmen in various media. The oldest dated etching is by Albrecht Dürer in 1515, although he returned to engraving after six etchings instead of developing the craft. The switch to copper plates was probably made in Italy, and thereafter etching soon came to challenge engraving as the most popular medium for artists in printmaking. Its great advantage was that, unlike engraving where the difficult technique for using the burin requires special skill in metalworking, the basic technique for creating the image on the plate in etching is relatively easy to learn for an artist trained in drawing. On the other hand, the handling of the ground and acid need skill and experience, and are not without health and safety risks, as well as the risk of a ruined plate. Prior to 1100 AD, the New World Hohokam independently utilized the technique of acid etching in marine shell designs. Jacques Callot from Nancy in Lorraine made important technical advances in etching technique. He developed the échoppe, a type of etching-needle with a slanting oval section at the end, which enabled etchers to create a swelling line, as engravers were able to do. Callot also appears to have been responsible for an improved, harder, recipe for the etching ground, using lute-makers' varnish rather than a wax-based formula.

more...