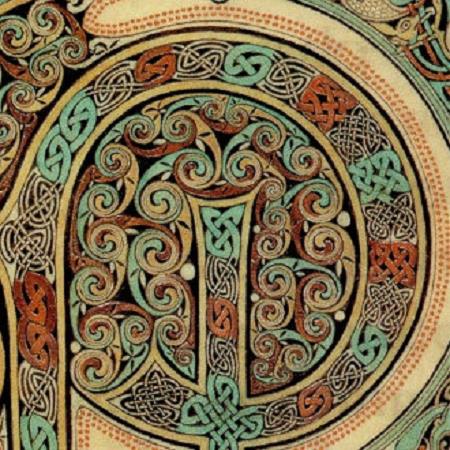

Anglo-Saxon Art. Anglo-Saxon art refers to the art produced in England between the 5th and 11th centuries, during the period of Anglo-Saxon rule. An example is the Sutton Hoo Ship Burial discovered in 1939 in Suffolk, England. The site contains a 90-foot-long ship filled with treasures, including gold and silver jewelry, weapons, and other artifacts. The most famous piece from the burial is the Sutton Hoo Helmet, an intricately decorated helmet made of iron, bronze, and gold. Another example is the Lindisfarne Gospels. Created in the late 7th or early 8th century, the Lindisfarne Gospels is an illuminated manuscript containing the four Gospels of the New Testament. The manuscript is notable for its elaborate decoration, which includes intricate patterns, animal motifs, and vibrant colors. The important artistic centres, in so far as these can be established, were concentrated in the extremities of England, in Northumbria, especially in the early period, and Wessex and Kent near the south coast. Anglo-Saxon art survives mostly in illuminated manuscripts, Anglo-Saxon architecture, a number of very fine ivory carvings, and some works in metal and other materials. Opus Anglicanum was already recognised as the finest embroidery in Europe, although only a few pieces from the Anglo-Saxon period remain-the Bayeux Tapestry is a rather different sort of embroidery, on a far larger scale. As in most of Europe at the time, metalwork was the most highly regarded form of art by the Anglo-Saxons, but hardly any survives-there was enormous plundering of Anglo-Saxon churches, monasteries and the possessions of the dispossessed nobility by the new Norman rulers in their first decades, as well as the Norsemen before them, and the English Reformation after them, and most survivals were once on the continent. Anglo-Saxon taste favoured brightness and colour, and an effort of the imagination is often needed to see the excavated and worn remains that survive as they once were. Perhaps the best known piece of Anglo-Saxon art is the Bayeux Tapestry which was commissioned by a Norman patron from English artists working in the traditional Anglo-Saxon style. Anglo-Saxon artists also worked in fresco, stone, ivory and whalebone, metalwork, glass and enamel, many examples of which have been recovered through archaeological excavation and some of which have simply been preserved over the centuries, especially in churches on the Continent, as the Vikings, Normans and Reformation iconoclasm between them left virtually nothing in England except for books and archaeological finds. Metalwork is almost the only form in which the earliest Anglo-Saxon art has survived, mostly in Germanic-style jewelry which was, before the Christianization of Anglo-Saxon England, commonly placed in burials. After the conversion, which took most of the 7th century, the fusion of Germanic Anglo-Saxon, Celtic and Late Antique techniques and motifs, together with the requirement for books, created Hiberno-Saxon style, or Insular art, which is also seen in illuminated manuscripts and some carved stone and ivory, probably mostly drawing from decorative metalwork motifs, and with further influences from the British Celts of the west and the Franks. The Kingdom of Northumbria in the far north of England was the crucible of Insular style in Britain, at centres such as Lindisfarne, founded c. 635 as an offshoot of the Irish monastery on Iona, and Monkwearmouth-Jarrow Abbey which looked to the continent. At about the same time as the Insular Lindisfarne Gospels was being made in the early 8th century, the Vespasian Psalter from Canterbury in the far south, which the missionaries from Rome had made their headquarters, shows a wholly different, classically based art. These two styles mixed and developed together and by the following century the resulting Anglo-Saxon style had reached maturity. However Anglo-Saxon society was massively disrupted in the 9th century, especially the later half, by the Viking invasions, and the number of significant objects surviving falls considerably, and their dating becomes even vaguer than of those from a century before.

more...