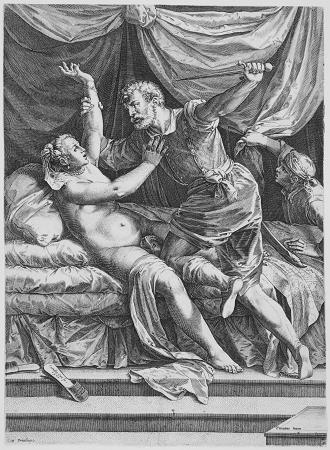

Lucretia (c-550 - c-510). According to Roman tradition, Lucretia, anglicized as Lucrece, was a noblewoman in ancient Rome whose rape by Sextus Tarquinius, an Etruscan king's son, was the cause of a rebellion that overthrew the Roman monarchy and led to the transition of Roman government from a kingdom to a republic. There are no contemporary sources; information regarding Lucretia, her rape and suicide, and the consequence of this being the start of the Roman Republic, come from the later accounts of Roman historian Livy and Greco-Roman historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus. The incident kindled the flames of dissatisfaction over the tyrannical methods of the last king of Rome, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus. As a result, the prominent families instituted a republic, drove the extensive royal family of Tarquin from Rome, and successfully defended the republic against attempted Etruscan and Latian intervention. As a result of its sheer impact, the rape itself became a major theme in European art and literature. One of the first two consuls of the Roman Republic, Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus was Lucretia's husband. All the numerous sources on the establishment of the republic reiterate the basic events of Lucretia's story, though accounts vary slightly. Lucretia's story is not considered a myth by most historians, but rather a historical legend about an early history that was already a major part of Roman folklore before it was first written about. The evidence points to the historical existence of a woman named Lucretia and a historical incident that played a critical part in the real downfall of a real monarchy. Many of the specific details, though, are debatable, and vary depending on the writer. Post-Roman uses of the legend typically became mythical in portrayal, being of artistic rather than historical merit. As the events of the story move rapidly, the date of the incident is probably the same year as the first of the fasti. Dionysius of Halicarnassus, a major source, sets this year at the beginning of the sixty-eighth Olympiad. Isagoras being the annual archon at Athens ; that is, 508/507 BC. Lucretia therefore died in 508 BC. The other historical sources tend to support this date, but the year is debatable within a range of about five years. Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, last king of Rome, being engaged in the siege of Ardea, sent his son, Tarquin, on a military errand to Collatia. Tarquin was received with great hospitality at the governor's mansion, home of Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus, son of the king's nephew, Arruns Tarquinius, former governor of Collatia and first of the Tarquinii Collatini. Collatinus' wife, Lucretia, daughter of Spurius Lucretius, prefect of Rome, a man of distinction, made sure that the king's son was treated as became his rank, although her husband was away at the siege. In a variant of the story, Tarquin and Collatinus, at a wine party on furlough, were debating the virtues of wives when Collatinus volunteered to settle the debate by all of them riding to his home to see what Lucretia was doing. She was weaving with her maids. The party awarded her the palm of victory and Collatinus invited them to visit, but for the time being they returned to camp. At night, Tarquin entered her bedroom by stealth, quietly going around the slaves who were sleeping at her door. She awakened. He identified himself and offered her two choices: she could submit to his sexual advances and become his wife and future queen, or he would kill her and one of her slaves and place the bodies together, then claim he had caught her having adulterous sex. In the alternative story, he returned from camp a few days later with one companion to take Collatinus up on his invitation to visit and was lodged in a guest bedroom. He entered Lucretia's room while she lay naked in her bed and started to wash her belly with water, which woke her up. Tarquin returned to camp. The next day Lucretia dressed in black and went to her father's house in Rome and cast herself down in the supplicant's position, weeping. Asked to explain herself, she insisted on first summoning witnesses and after disclosing the rape, called on them for vengeance, a plea that could not be ignored, as she was speaking to the chief magistrate of Rome. While they were debating the proper course of action, she drew a concealed dagger and stabbed herself in the heart. She died in her father's arms, with the women present keening and lamenting. This dreadful scene struck the Romans who were present with so much horror and compassion that they all cried out with one voice that they would rather die a thousand deaths in defence of their liberty than suffer such outrages to be committed by the tyrants.

more...