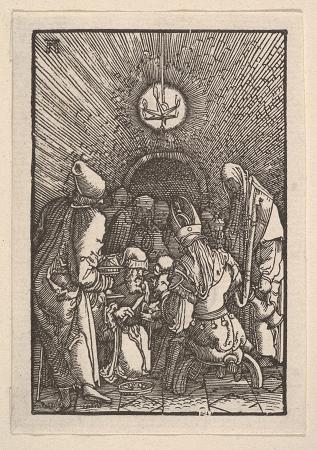

Circumcision of Jesus. The circumcision of Jesus is an event from the life of Jesus, according to the Gospel of Luke chapter 2, which states in verse 21 that Jesus was circumcised eight days after his birth. This is in keeping with the Jewish law which holds that males should be circumcised eight days after birth during a Brit milah ceremony, at which they are also given their name. The circumcision of Christ became a very common subject in Christian art from the 10th century onwards, one of numerous events in the Life of Christ to be frequently depicted by artists. It was initially seen only as a scene in larger cycles, but by the Renaissance might be treated as an individual subject for a painting, or form the main subject in an altarpiece. The event is celebrated as the Feast of the Circumcision in the Eastern Orthodox Church on January 1 in whichever calendar is used, and is also celebrated on the same day by many Anglicans. It is celebrated by Roman Catholics as the Feast of the Holy Name of Jesus, in recent years on January 3 as an Optional Memorial, though it was for long celebrated on January 1, as some other churches still do. A number of relics claiming to be the Holy Prepuce, the foreskin of Jesus, have surfaced. The second chapter of the Gospel of Luke records the circumcision of Jesus: And when eight days were accomplished for the circumcising of the child, his name was called Jesus, which was so named of the angel before he was conceived in the womb. However, this account is extremely short, particularly compared to Paul the Apostle's much fuller description of his own circumcision in the third chapter of his Epistle to the Philippians. This led theologians Friedrich Schleiermacher and David Strauss to speculate that the author of the Gospel of Luke might have assumed the circumcision to be historical fact, or might have been relating it as recalled by someone else. In addition to the canonical account in the Gospel of Luke, the apocryphal Arabic Infancy Gospel contains the first reference to the survival of Christ's severed foreskin. The second chapter has the following story: And when the time of his circumcision was come, namely, the eighth day, on which the law commanded the child to be circumcised, they circumcised him in a cave. And the old Hebrew woman took the foreskin, and preserved it in an alabaster-box of old oil of spikenard. And she had a son who was a druggist, to whom she said, Take heed thou sell not this alabaster box of spikenard-ointment, although thou shouldst be offered three hundred pence for it. Now this is that alabaster-box which Mary the sinner procured, and poured forth the ointment out of it upon the head and feet of our Lord Jesus Christ, and wiped it off with the hairs of her head. The circumcision controversy in early Christianity was resolved in the 1st century, so that non-Jewish Christians were not obliged to be circumcised. Saint Paul, the leading proponent of this position, discouraged circumcision as a qualification for conversion to Christianity. Circumcision soon became rare in most of the Christian world, except the Coptic Church of Egypt and for Judeo-Christians. Perhaps for this reason, the subject of the circumcision of Christ was extremely rare in Christian art of the 1st millennium, and there appear to be no surviving examples until the very end of the period, although literary references suggest it was sometimes depicted. One of the earliest depictions to survive is a miniature in an important Byzantine illuminated manuscript of 979-984, the Menologion of Basil II in the Vatican Library. This has a scene which shows Mary and Joseph holding the baby Jesus outside a building, probably the Temple of Jerusalem, as a priest comes towards them with a small knife. This is typical of the early depictions, which avoid showing the operation itself. At the period of Jesus's birth, the actual Jewish practice was for the operation to be performed at home, usually by the father, and Joseph is shown using the knife in an enamelled plaque from the Klosterneuburg Altar by Nicolas of Verdun, where it is next to plaques showing the very rare scenes of the circumcisions of Isaac and Samson. Like most later depictions these are shown taking place in a large building, probably representing the Temple, though in fact the ceremony was never performed there. Medieval pilgrims to the Holy Land were told Jesus had been circumcised in the church at Bethlehem. The scene gradually became increasingly common in the art of the Western church, and increasingly rare in Orthodox art.

more...