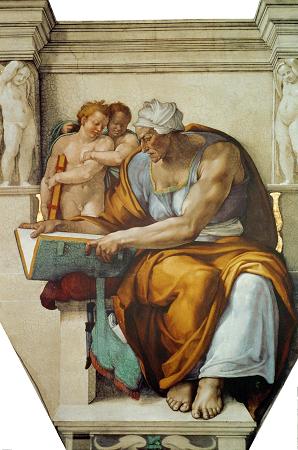

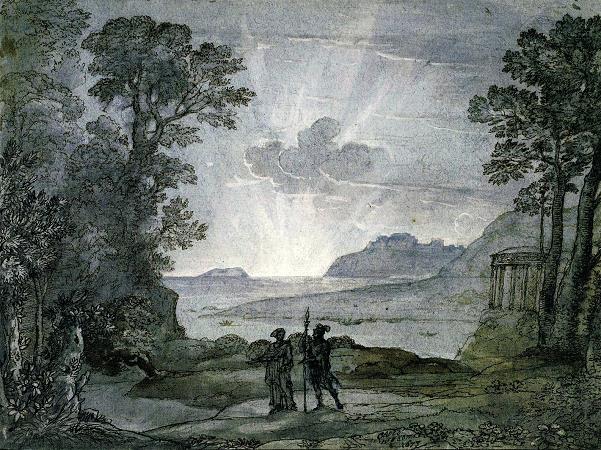

Cumaean Sibyl. The Cumaean Sibyl was the priestess presiding over the Apollonian oracle at Cumae, a Greek colony located near Naples, Italy. The word sibyl comes from the ancient Greek word sibylla, meaning prophetess. There were many sibyls in different locations throughout the ancient world. Because of the importance of the Cumaean Sibyl in the legends of early Rome as codified in Virgil's Aeneid VI, and because of her proximity to Rome, the Cumaean Sibyl became the most famous among the Romans. The Erythraean Sibyl from modern-day Turkey was famed among Greeks, as was the oldest Hellenic oracle, the Sibyl of Dodona, possibly dating to the second millennium BC according to Herodotus, favored in the east. The Cumaean Sibyl is one of the four sibyls painted by Raphael at Santa Maria della Pace She was also painted by Andrea del Castagno, and in the Sistine Ceiling of Michelangelo her powerful presence overshadows every other sibyl, even her younger and more beautiful sisters, such as the Delphic Sibyl. There are various names for the Cumaean Sibyl besides the Herophile of Pausanias and Lactantius or the Aeneid' s Deiphobe, daughter of Glaucus : Amaltheia, Demophile or Taraxandra are all offered in various references. The story of the acquisition of the Sibylline Books by Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, the semi-legendary last king of the Roman Kingdom, or Tarquinius Priscus, is one of the famous mythic elements of Roman history. Centuries ago, concurrent with the 50th Olympiad, not long before the expulsion of Rome's kings, an old woman who was not a native of the country arrived incognita in Rome. She offered nine books of prophecies to King Tarquin; and as the king declined to purchase them, owing to the exorbitant price she demanded, she burned three and offered the remaining six to Tarquin at the same stiff price, which he again refused, whereupon she burned three more and repeated her offer. Tarquin then relented and purchased the last three at the full original price, whereupon she disappeared from among men. The books were thereafter kept in the Temple of Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill, Rome, to be consulted only in emergencies. The temple burned down in the 80s BC, and the books with it, necessitating a re-collection of Sibylline prophecies from all parts of the empire. These were carefully sorted and those determined to be legitimate were saved in the rebuilt temple. The Emperor Augustus had them moved to the Temple of Apollo on the Palatine Hill, where they remained for most of the remaining Imperial Period. The Cumaean Sibyl is featured in the works of various Roman authors, including Virgil, Ovid and Petronius. The Cumaean Sibyl prophesied by singing the fates and writing on oak leaves. These would be arranged inside the entrance of her cave, but if the wind blew and scattered them, she would not help to reassemble the leaves and recreate the original prophecy. The Sibyl was a guide to the underworld, whose entrance lay at the nearby crater of Avernus. Aeneas employed her services before his descent to the lower world to visit his dead father Anchises, but she warned him that it was no light undertaking: Trojan, Anchises' son, the descent of Avernus is easy. All night long, all day, the doors of Hades stand open. But to retrace the path, to come up to the sweet air of heaven, That is labour indeed., Aeneid 6.126-129. The Sibyl acts as a bridge between the worlds of the living and the dead. She shows Aeneas the way to Avernus and teaches him what he needs to know about the dangers of their journey. Although she was a mortal, the Sibyl lived about a thousand years. She attained this longevity when Apollo offered to grant her a wish in exchange for her virginity; she took a handful of sand and asked to live for as many years as the grains of sand she held. Later, after she refused the god's love, he allowed her body to wither away because she failed to ask for eternal youth. Her body grew smaller with age and eventually was kept in a jar. Eventually only her voice was left. Virgil may have been influenced by Hebrew texts, according to Tacitus, amongst others. Constantine, the Christian emperor, in his first address to the assembly, interpreted the whole of The Eclogues as a reference to the coming of Christ, and quoted a long passage of the Sibylline Oracles containing an acrostic in which the initials from a series of verses read: Jesus Christ Son of God Saviour Cross.

more...