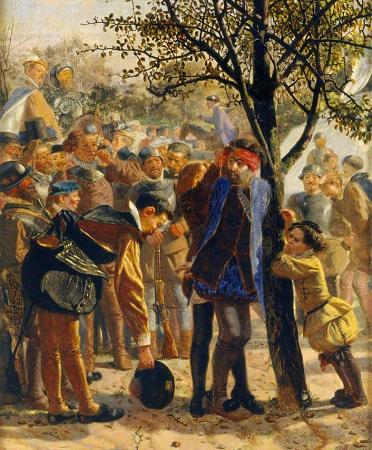

All's Well That Ends Well (c1605). All's Well That Ends Well is a play by William Shakespeare, published in the First Folio in 1623, where it is listed among the comedies. There is a debate regarding the dating of the composition of the play, with possible dates ranging from 1598 to 1608. The play is considered one of Shakespeare's problem plays; a play that poses complex ethical dilemmas that require more than typically simple solutions. King of France. Duke of Florence. Bertram, Count of Roussillon. Countess of Roussillon, Mother of Bertram. Lavatch, a Clown in her household. Helena, a Gentlewoman protected by the Countess. Lafew, an old Lord. Parolles, a follower of Bertram. An Old Widow of Florence, surnamed Capilet. Diana, Daughter of the Widow. Steward of the Countess of Roussillon. Violenta and Mariana, Neighbours and Friends of the Widow. A Page. Soldiers, Servants, Gentlemen, and Courtiers. Helena, the low-born ward of a French-Spanish countess, is in love with the countess's son Bertram, who is indifferent to her. Bertram goes to Paris to replace his late father as attendant to the ailing King of France. Helena, the daughter of a recently deceased physician, follows Bertram, ostensibly to offer the King her services as a healer. The King is sceptical, and she guarantees the cure with her life: if he dies, she will be put to death, but if he lives, she may choose a husband from the court. The King is cured and Helena chooses Bertram, who rejects her, owing to her poverty and low status. The King forces him to marry her, but after the ceremony Bertram immediately goes to war in Italy without so much as a goodbye kiss. He says that he will only marry her after she has borne his child and wears his family ring. Helena returns home to the countess, who is horrified at what her son has done, and claims Helena as her child in Bertram's place. In Italy, Bertram is a successful warrior and also a successful seducer of local virgins. Helena follows him to Italy, befriends Diana, a virgin with whom Bertram is infatuated, and they arrange for Helena to take Diana's place in bed. Diana obtains Bertram's ring in exchange for one of Helena's. In this way Helena, without Bertram's knowledge, consummates their marriage and wears his ring. Helena fakes her own death. Bertram, thinking he is free of her, comes home. He tries to marry a local lord's daughter, but Diana shows up and breaks up the engagement. Helena appears and explains the ring swap, announcing that she has fulfilled Bertram's challenge; Bertram, impressed by all she has done to win him, swears his love to her. Thus all ends well. There is a subplot about Parolles, a disloyal associate of Bertram's: Some of the lords at the court attempt to get Bertram to know that his friend Parolles is a boasting coward, as Lafew and the Countess have also said. They convince Parolles to cross into enemy territory to fetch a drum that he left behind. While on his way, they pose as enemy soldiers, kidnap him, blindfold him, and, with Bertram observing, get him to betray his friends, and besmirch Bertram's character. The play is based on a tale of Boccaccio's The Decameron. Shakespeare may have read an English translation of the tale in William Painter's Palace of Pleasure. There is no evidence that All's Well That Ends Well was popular in Shakespeare's own lifetime and it has remained one of his lesser-known plays ever since, in part due to its unorthodox mixture of fairy tale logic, gender role reversals and cynical realism. Helena's love for the seemingly unlovable Bertram is difficult to explain on the page, but in performance it can be made acceptable by casting an actor of obvious physical attraction or by playing him as a naive and innocent figure not yet ready for love although, as both Helena and the audience can see, capable of emotional growth. This latter interpretation also assists at the point in the final scene in which Bertram suddenly switches from hatred to love in just one line. This is considered a particular problem for actors trained to admire psychological realism. However, some alternative readings emphasise the if in his equivocal promise: If she, my liege, can make me know this clearly, I'll love her dearly, ever, ever dearly. Here, there has been no change of heart at all. Productions like the National Theatre's 2009 run, have Bertram make his promise seemingly normally, but then end the play hand-in-hand with Helena, staring out at the audience with a look of aghast bewilderment suggesting he only relented to save face in front of the King.

more...