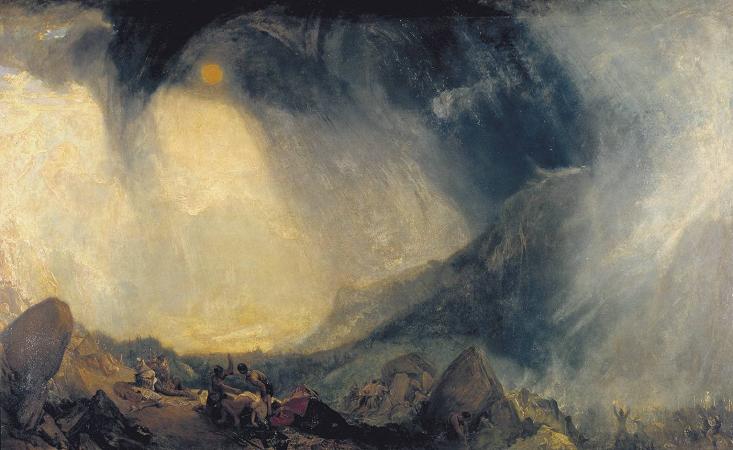

Hannibal and Army Crossing Alps (1812). Oil on canvas. 146 x 239. Snow Storm: Hannibal and his Army Crossing the Alps is an oil on canvas painting by J. M. W. Turner, first exhibited in 1812. Left to the nation in the Turner Bequest, it was acquired by the National Gallery in London in 1856, and is now held by the Tate Gallery. The painting depicts the struggle of Hannibal's soldiers to cross the Maritime Alps in 218BC, opposed by the forces of nature and local tribes. A curving black storm cloud dominates the sky, poised to descend on the soldiers in the valley below, with an orange-yellow Sun attempting to break through the clouds. A white avalanche cascades down the mountain to the right. Hannibal himself is not clearly depicted, but may be riding the elephant just visible in the distance. The large animal is dwarfed by the storm and the landscape, with the sunlit plains of Italy opening up beyond. In the foreground, Salassian tribesmen are fighting Hannibal's rearguard, confrontations that are described in the histories of Polybius and Livy. The painting measures 146 × 237.5 centimetres. It contains the first appearance in Turner's work of a swirling oval vortex of wind, rain and cloud, a dynamic composition of contrasting light and dark that will recur in later works, such as his 1842 painting Snow Storm: Steam-Boat off a Harbour's Mouth. Turner saw parallels between Hannibal and Napoleon, and between the historic Punic War between Rome and Carthage and the contemporary Napoleonic Wars between Britain and France. The painting is Turner's response to Jacques-Louis David's portrait of Napoleon Crossing the Alps, of Napoleon leading his army over the Great St Bernard Pass in May 1800, which Turner had seen during a visit to Paris in 1802. Turner set his painting in the Val d'Aosta, one of the possible routes that Hannibal may have used to cross the Alps, which Turner had also visited in 1802. Identifying Napoleon and France with Hannibal and Carthage was unusual: as a land power with a relatively weak navy, France was more usually identified with Rome, and the naval power of Britain drew parallels with Carthage. A more typical symbolism, linking the modern naval power of Britain with the ancient naval power of Carthage, can be detected in Turner's later works, Dido Building Carthage, and The Decline of the Carthaginian Empire. The irregular composition, without geometric axes or perspective, breaks traditional rules of composition. It is similar to Turner's 1800-2 watercolour, Edward I's Army in Wales, painted to illustrate a passage from the poem The Bard by Thomas Gray, in which an army marches diagonally across the painting through a mountain pass, and is assailed by an archer to the left of the painting. Turner sketched out the foreground figures as early as 1804, and had observed an impressive storm from Farnley Hall, the house of Walter Fawkes in Yorkshire, in 1810; making notes on the back of a letter, he remarked to Fawkes' son Hawkesworth that its like would be seen again in two years, and it would be called Hannibal crossing the Alps. Turner may also have been inspired by a lost oil painting of Hannibal's army descending the Alps into northern Italy by watercolourist John Robert Cozens, A Landscape with Hannibal in His March over the Alps, Showing to His Army the Fertile Plains of Italy, the only oil painting that Cozens exhibited at the Royal Academy, and also an entry in list of imaginary paintings written by Thomas Gray, which speculated that Salvator Rosa could have painted Hannibal passing the Alps. Another spur to make the painting could have been the visit of a delegation from the Tyrol to London in 1809, seeking support to oppose Napoleon. The painting was first exhibited at the Royal Academy summer exhibition at Somerset House in 1812, accompanied in the catalogue with some lines from Turner's unfinished epic poem Fallacies of Hope: Craft, treachery, and fraud-Salassian force, Hung on the fainting rear! then Plunder seiz'd The victor and the captive,-Saguntum's spoil, Alike, became their prey; still the chief advanc'd, Look'd on the sun with hope;-low, broad, and wan; While the fierce archer of the downward year Stains Italy's blanch'd barrier with storms. In vain each pass, ensanguin'd deep with dead, Or rocky fragments, wide destruction roll'd. Still on Campania's fertile plains-he thought, But the loud breeze sob'd, Capua's joys beware! Turner insisted that the painting should be hung low on the wall at the exhibition to ensure it would be viewed from the correct angle. It was widely praised as impressive, terrible, magnificent and sublime. The painting was left to the nation in the Turner Bequest in 1856, and held by the National Gallery until it was transferred to the Tate Gallery in 1910.

more...