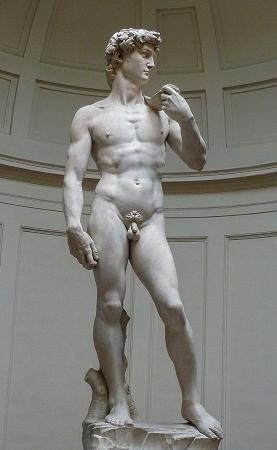

David (c1440). Bronze. 160. David is the title of two statues of the biblical hero David by the Italian early Renaissance sculptor Donatello. They consist of an early work in marble of a clothed figure, and a far more famous bronze figure that is nude except for helmet and boots, and dates to the 1440s or later. Both are now in the Museo Nazionale del Bargello in Florence. The story of David and Goliath comes from 1 Samuel 17. The Israelites are fighting the Philistines, whose champion-Goliath-repeatedly offers to meet the Israelites' best warrior in single combat to decide the whole battle. None of the trained Israelite soldiers are brave enough to fight the giant Goliath, until David-a shepherd boy who is too young to be a soldier-accepts the challenge. Saul, the Israelite leader, offers David armor and weapons, but the boy is untrained and refuses them. Instead, he goes out with his sling, and confronts the enemy. He hits Goliath in the head with a stone, knocking the giant down, and then grabs Goliath's sword and cuts off his head. The Philistines withdraw as agreed and the Israelites are saved. David's special strength comes from God, and the story illustrates the triumph of good over evil. Donatello, then in his early twenties, was commissioned to carve a statue of David in 1408, to top one of the buttresses of Florence Cathedral, though it was never placed there. Nanni di Banco was commissioned to carve a marble statue of Isaiah, at the same scale, in the same year. One of the statues was lifted into place in 1409, but was found to be too small to be easily visible from the ground and was taken down; both statues then languished in the workshop of the opera for several years. In 1416, the Signoria of Florence commanded that the David be sent to the Palazzo della Signoria; evidently the young David was seen as an effective political symbol, as well as a religious hero. Donatello was asked to make some adjustments to the statue, and a pedestal with an inscription was made for it: PRO PATRIA FORTITER DIMICANTIBUS ETIAM ADVERSUS TERRIBILISSIMOS HOSTES DII PRAESTANT AUXILIUM. The marble David is Donatello's earliest known important commission, and it is a work closely tied to tradition, giving few signs of the innovative approach to representation that the artist would develop as he matured. Although the positioning of the legs hints at a classical contrapposto, the figure stands in an elegant Gothic sway that surely derives from Lorenzo Ghiberti. The face is curiously blank, and David seems almost unaware of the head of his vanquished foe that rests between his feet. Some scholars have seen an element of personality-a kind of cockiness-suggested by the twist of the torso and the akimbo placement of the left arm, but overall the effect of the figure is rather bland. The head of Goliath, lying at David's feet, is carved with great assurance and reveals the young sculptor's genuinely Renaissance interest in an ancient Roman type of mature, bearded head. Donatello's bronze statue of David is famous as the first unsupported standing work of bronze cast during the Renaissance, and the first freestanding nude male sculpture made since antiquity. It depicts David with an enigmatic smile, posed with his foot on Goliath's severed head just after defeating the giant. The youth is completely naked, apart from a laurel-topped hat and boots, and bears the sword of Goliath. The creation of the work is undocumented. Most scholars assume the statue was commissioned by Cosimo de' Medici, but the date of its creation is unknown and widely disputed; suggested dates vary from the 1420s to the 1460s, with the majority opinion recently falling in the 1440s, when the new Medici Palace designed by Michelozzo was under construction. According to one theory, it was commissioned by the Medici family in the 1430s to be placed in the center of the courtyard of the old Medici Palace. Alternatively it may have been made for that position in the new Palazzo Medici, where it was placed later, which would place the commission in the mid-1440s or even later. The statue is only recorded there by 1469. The Medici family were exiled from Florence in 1494, and the statue was moved to the courtyard of the Palazzo della Signoria. It was moved to the Palazzo Pitti in the 17th century, to the Uffizi in 1777, and then finally, in 1865, to the Museo Nazionale del Bargello, where it remains today. According to Vasari, the statue stood on a column designed by Desiderio da Settignano in the middle of the courtyard of the Palazzo Medici; an inscription seems to have explained the statue's significance as a political monument.

more...